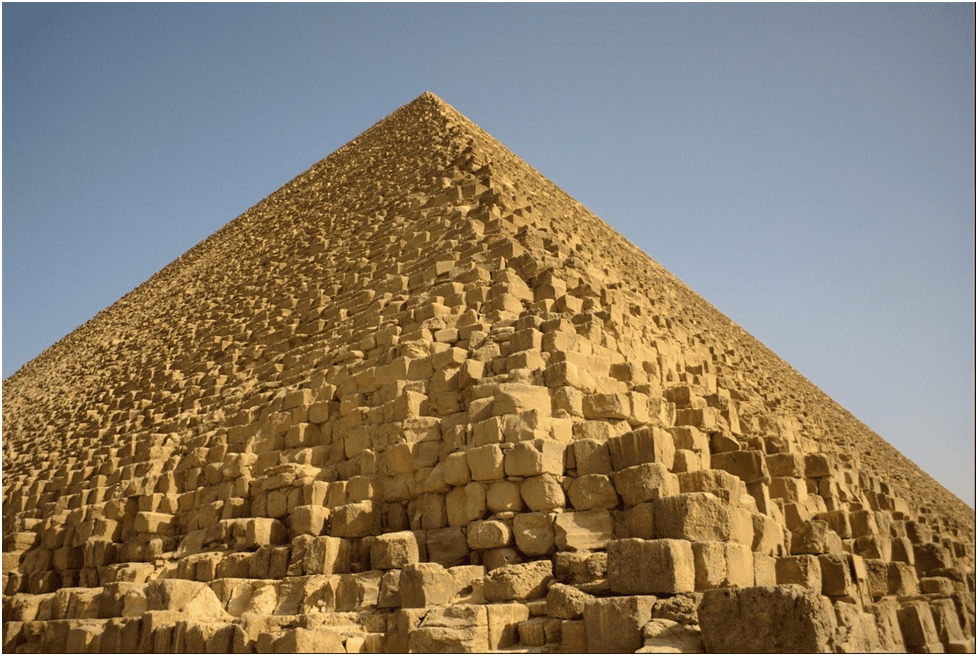

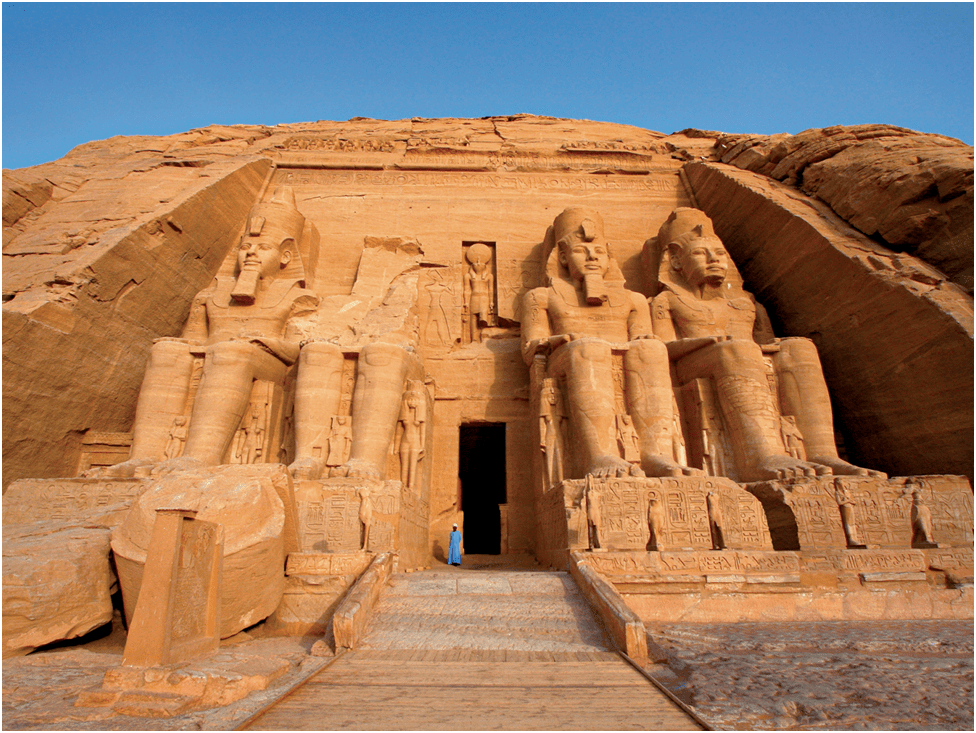

The popular view of life in ancient Egypt is often that it was a death-obsessed culture in which powerful pharaohs forced the people to labor at constructing pyramids and temples and, at an unspecified time, enslaved the Hebrews for this purpose.

In reality, ancient Egyptians loved life, no matter their social class, and the ancient Egyptian government used slave labor as every other ancient culture did without regard to any particular ethnicity. The ancient Egyptians did have a well-known contempt for non-Egyptians but this was simply because they believed they were living the best life possible in the best of all possible worlds.

Life in ancient Egypt was considered so perfect, in fact, that the Egyptian afterlife was imagined as an eternal continuation of life on earth. Slaves in Egypt were either criminals, those who could not pay their debts, or captives from foreign military campaigns. These people were considered to have forfeited their freedoms either by their individual choices or by military conquest and so were forced to endure a quality of existence far below that of free Egyptians.

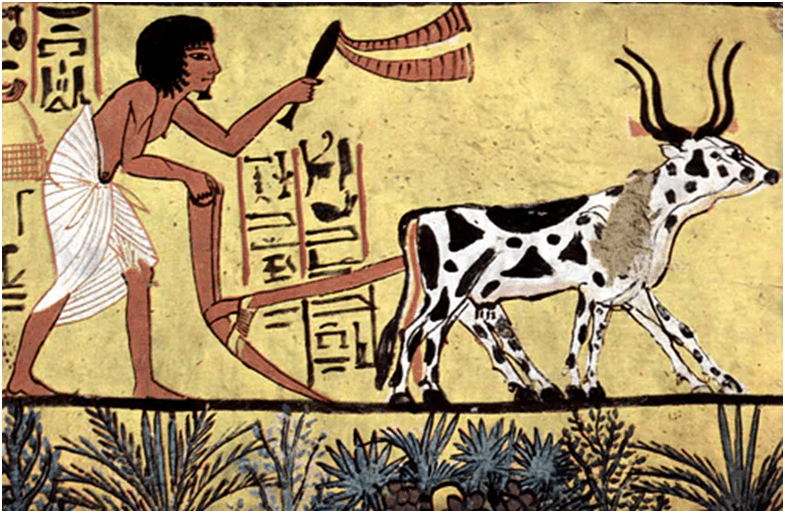

The individuals who actually built the pyramids and other famous monuments of Egypt were Egyptians who were compensated for their labor and, in many cases, were masters of their art. These monuments were raised not in honor of death but of life and the belief that an individual life mattered enough to be remembered for eternity. Further, the Egyptian belief that one’s life was an eternal journey and death only a transition inspired the people to try to make their lives worth living eternally. Far from a death-obsessed and dour culture, Egyptian daily life was focused on enjoying the time one had as much as possible and trying to make other’s lives equally memorable.

Sports, games, reading, festivals, and time with one’s friends and family were as much a part of Egyptian life as toil in farming the land or erecting monuments and temples. The world of the Egyptians was imbued with magic. Magic (heka) predated the gods and, in fact, was the underlying force which allowed the gods to perform their duties.

Magic was personified in the god Heka (also the god of medicine) who had participated in the creation and sustained it afterwards. The concept of ma’at (harmony and balance) was central to the Egyptian’s understanding of life and the operation of the universe and it was heka which made ma’at possible. Through the observance of balance and harmony people were encouraged to live at peace with others and contribute to communal happiness. A line from the wisdom text of Ptahhotep (the vizier to the king Djedkare Isesi, 2414-2375 BCE), admonishes a reader:

Letting one’s face “shine” meant being happy, having a good spirit, in the belief that this would make one’s own heart light and lighten those of others. Although Egyptian society was highly stratified from a very early period (as early as the Predynastic Period in Egypt of c. 6000-3150 BCE), this does not mean that the royalty and upper classes enjoyed their lives at the expense of the peasantry.

Population & Social Classes

The population of Egypt was strictly divided into social classes from the king at the top, his vizier, the members of his court, regional governors (eventually called ‘nomarchs’), the generals of the military (after the period of the New Kingdom), government overseers of worksites (supervisors), and the peasantry. Social mobility was neither encouraged nor observed for most of Egypt’s history as it was thought that the gods had decreed the most perfect social order which mirrored that of the gods.

The gods had given the people everything and had set the king over them as the one best-equipped to understand and implement their will. The king was the intermediary between the gods and the people from the Predynastic Period through the Old Kingdom (c. 2613-2181 BCE) when the priests of the sun god Ra began to gain more power. Even after this, however, the king was still considered god’s chosen emissary. Even the latter part of the New Kingdom (1570-1069 BCE) when the priests of Amun at Thebes held greater power than the king, the monarch was still respected as divinely ordained.

Upper class

The king of Egypt (not known as a ‘pharaoh’ until the New Kingdom period), as the gods’ chosen man, “enjoyed great wealth and status and luxuries unimaginable to the majority of the population” (Wilkinson, 91). It was the king’s responsibility to rule in keeping with ma’at, and as this was a serious charge, he was thought to deserve those luxuries in keeping with his status and the weight of his duties. Historian Don Nardo writes:

The king is often depicted hunting and inscriptions regularly boast of the number of large and dangerous animals a particular monarch killed during his reign. Almost without exception, though, animals like lions and elephants were caught by royal game wardens and brought to preserves where the king then “hunted” the beasts while surrounded by guards who protected him. The king would hunt in the open, for the most part, only once the area had been cleared of dangerous animals.

Members of the court lived in similar comfort, although most of them had little responsibility. The nomarchs might also live well, but this depended on how wealthy their particular district was and how important to the king. The nomarch of a district including a site such as Abydos, for example, would expect to do quite well because of the large necropolis there dedicated to the god Osiris, which brought many pilgrims to the city including the king and courtiers. A nomarch of a region which had no such attraction would expect to live more modestly. The wealth of the region and the personal success of an individual nomarch would determine whether they lived in a small palace or a modest home. This same model applied generally to scribes.

Scribes & Physicians

Scribes were valued highly in ancient Egypt as they were considered specially chosen by the god Thoth, who inspired and presided over their craft. Egyptologist Toby Wilkinson notes how “the power of the written word to render permanent a desired state of affairs lay at the heart of Egyptian belief and practice” (204). It was the scribes’ responsibility to record events so they would become permanent. The words of the scribes etched daily events in the record of eternity since it was thought that Thoth and his consort Seshat kept the scribes’ words in the eternal libraries of the gods.

A scribe’s work made him or her immortal not only because later generations would read what they wrote but because the gods themselves were aware of it. Seshat, patron goddess of libraries and librarians, carefully placed one’s work on her shelves, just as librarians in her service did on earth. Most scribes were male, but there were female scribes who lived just as comfortably as their male counterparts. A popular piece of literature from the Old Kingdom, known as Duauf’s Instructions, advocates a love for books and encourages young people to pursue higher learning and become scribes in order to live the best life possible.

All priests were scribes, but not all scribes became priests. The priests needed to be able to read and write to perform their duties, especially concerning mortuary rituals. As doctors needed to be literate to read medical texts, they began their training as scribes. Most diseases were thought to be inflicted by the gods as punishment for sin or to teach a lesson, and so doctors needed to be aware of which god (or evil spirit, or ghost, or other supernatural agent) might be responsible.

In order to perform their duties, they had to be able to read the religious literature of the time, which includes works on dentistry, surgery, the setting of broken bones, and the treatment of various illnesses. As there was no separation between one’s religious and daily life, doctors were usually priests until later in Egypt’s history when there is a secularization of the profession.

All of the priests of the goddess Serket were doctors and this practice continued even after the emergence of more secular physicians. As in the case of scribes, women could practice medicine, and female doctors were numerous. In the 4th century BCE, Agnodice of Athens famously traveled to Egypt to study medicine since women were held in higher regard and had more opportunity there than in Greece.

Military

The military prior to the Middle Kingdom was made up of regional militias conscripted by nomarchs for a certain purpose, usually defense, and then sent to the king. At the beginning of the 12th Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom, Amenemhat I (c. 1991-c.1962 BCE) reformed the military to create the first standing army, thus decreasing the power and prestige of the nomarchs and putting the army directly under his control.

After this, the military was made up of upper-class leaders and lower-class rank and file members. There was the possibility of advancement in the military, which was not affected by one’s social class. Prior to the New Kingdom, the Egyptian military was primarily concerned with defense, but pharaohs like Tuthmose III (1458-1425 BCE) and Ramesses II (1279-1213 BCE) led campaigns beyond Egypt’s borders in expanding the empire. Egyptians generally avoided travel to other lands because they feared that, if they should die there, they would have greater difficulty reaching the afterlife. This belief was a definite concern of soldiers on foreign campaigns and provisions were made to return the bodies of the dead to Egypt for burial.

There is no evidence that women served in the military or, according to some accounts, would have wanted to. The Papyrus Lansing, to give only one example, describes life in the Egyptian army as unending misery leading to an early death. It should be noted, however, that scribes (especially the author of the Papyrus Lansing) consistently depicted their job as the best and most important, and it was the scribes who left behind most of the reports on military life

Farmers & Laborers

The lowest social class was made up of peasant farmers who did not own the land they worked or the homes they lived in. The land was owned by the king, members of the court, nomarchs, or priests. A common phrase of the peasants to start the day was “Let us work for the noble!” The peasants were almost all farmers, no matter what other trade they cultivated (ferryman, for example). They planted and harvested their crops, gave most of it to the land owner, and kept some for themselves. Most had private gardens, which women tended while the men went out to the fields.

Up until the time of the Persian invasion of 525 BCE, the Egyptian economy operated on the barter system and was based on agriculture. The monetary unit of ancient Egypt was the deben, which according to historian James C. Thompson, “functioned much as the dollar does in North America today to let customers know the price of things, except that there was no deben coin” (Egyptian Economy, 1). A deben was “approximately 90 grams of copper; very expensive items could also be priced in debens of silver or gold with proportionate changes in value” (ibid). Thompson continues.

Apart from this, if you are interested to know about Enhancing Business Efficiency with Best IT Support Services Provider in Australia then visit our Business category.